Aerial view of Iklaina: This palace dating to around 3400 years ago shows the city was no backwater, as had been thought, but a powerful Mycaenean-era capital in competition with the Palace of Nestor, Michael Cosmopoulos

Aerial view of Iklaina: This palace dating to around 3400 years ago shows the city was no backwater, as had been thought, but a powerful Mycaenean-era capital in competition with the Palace of Nestor, Michael Cosmopoulos

Massive buildings, early writing show Iklaina wasn’t a backwater as thought, but a center of Mycenaean rule that was destroyed by the Palace of Nestor, archaeologists say.

Monumental discoveries in Iklaina, including an open-air pagan sanctuary, have reinforced the view that this ancient Greek town was no backwater as had been thought, but a major center of Mycenaean culture – that throws back the formation of the earliest complex states in ancient Greece by hundreds of years.

Iklaina was made legendary by Homer’s Iliad, which romanticizes the town’s war with Troy. Until now the town, which indeed dates to the Mycenaean period (1500 to 1100 B.C.E.), had been considered to be something of a backwater. Evidently, it wasn’t.

The true lofty status of ancient Iklaina now coming to light is based on discovery of a monumental palace and other massive buildings that apparently served as administrative centers; a tablet with the earliest-known government record in Europe, discovered in 2011; and newly uncovered sprawling public spaces such as the sanctuary, the archaeologists explain.

Complex states feature centralized political administration, specialized administrative organization, complex social ranking, advanced economic organization, and formalized institutions. If until now, the earliest complex state in ancient Greece had been thought to have arisen around 3,100 years ago, the evidence from Iklaina indicates that the complex states were taking form as long as 3,400 years ago, though that was thousands of years after these forms of government began to arise in Mesopotamia, going by the solid evidence.

“It appears that Iklaina was the capital of an independent state for a good part of the Mycenaean period, in competition with the other major site in the area, the Palace of Nestor in Pylos,” says Prof. Michael Cosmopoulos of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, head of the excavations.

Apparently, Iklaina was ultimately vanquished by that next-door bitter rival. It was destroyed by enemy attack at the same time that the Palace of Nestor expanded, Cosmopoulos explains: “It appears that the two events were connected, and that it was the ruler of the Palace of Nestor who took over Iklaina.”

The excavations at Iklaina brought to light massive walls, several administrative buildings, open-air shrine, murals, a surprisingly advanced drainage system with massive stone-built sewers, and an elaborate water delivery system with clay pipes that was far ahead of its time. The tablet the Iklaina archaeologists discovered, which they believe to be 3400 to 3500 years old, also throws back the advent of widespread literacy across this region of the eastern Mediterranean Basin.

The legend of Nestor

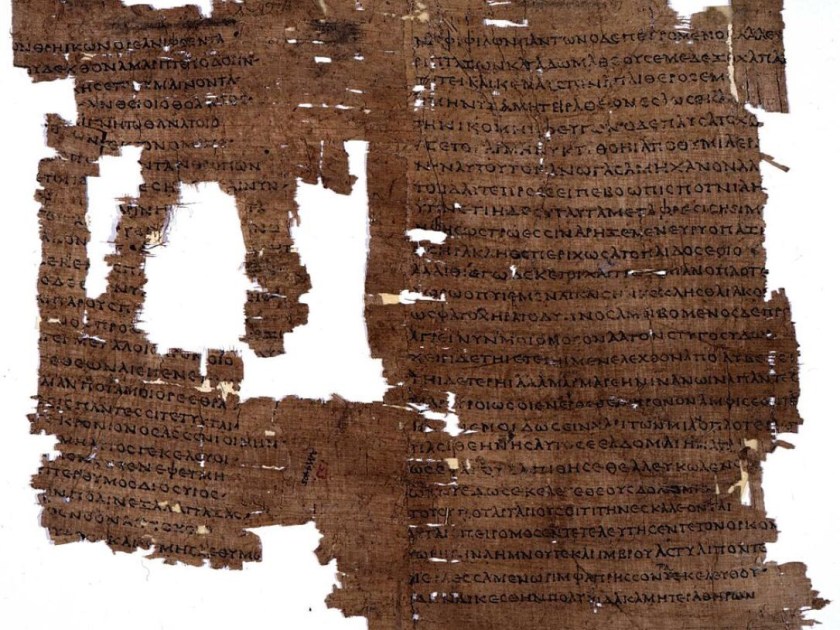

Page from the Iliad, XIV,227–253,256–263, written on papyrus in Greek. Wikimedia Commons.

Nestor is one of the main figures in the Homeric tale of Troy. After King Menelaos’ beautiful wife Helene was abducted by the Trojan prince Paris, who also plundered the palace treasures while about it, the king set out to gain revenge, first turning to his brother, the powerful king of Mycenae, Agamemnon.

The two together went to plead before the old king Nestor, the most experienced of all humans, because he had seen two generations sink into the grave and now reigned with unbroken force over the third. Nestor willingly helped the two brothers muster allies among the Greek lords and heroes.

Map showing Iklaina and the Palace of Nestor in mainland ancient Greece Google Maps, elaboration by Haaretz.

There is no archaeological evidence of Nestor to back the Homeric writings, but Cosmopoulos does not rule him out as a historical figure.

“Quite a bit of what is described in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey is based on the historical reality of the Mycenaean world: this applies to artifacts described by Homer, to citadels like Mycenae and Pylos, which archaeologists have found,” he says.

That said, Homer wrote his epics about 400 years after the Mycenaeans. The epics therefore contain anachronisms, elements contemporary to Homer which did not exist in the Mycenaean period, for example the use of iron or cremating the dead, Cosmopoulos explains.

The so-called “Palace of Nestor” in Pylos, some 10 kilometers from Iklaina, may or may not have housed the legendary wise king, but it definitely was a major palace of the Mycenaean period. The Pylos site has yielded over 1,000 Linear B tablets containing government records, dating 150 to 200 years later than the Iklaina tablet.

At the grand Palace of Nestor, Pylos, just 10km from Iklaina. Olecorre, Wikimedia Commons.

Giant Cyclopean Terrace

Eight years of excavations ending in late 2016 unearthed more of an enormous building that the archaeologist labeled the Cyclopean Terrace, which dominates the entire site. The terrace consists of worked limestone boulders fitted roughly together, with smaller chunks placed between them.

(The ancients coming some generations after the walls had been built did not believe that such massive structures could have been built by humans, but had to have been the work of gigantic beings such as the Cyclops. The term “Cyclopean” has come to refer to that particular type of Mycenaean large-scale architecture.)

Whoever built it, the massive Cyclopean Terrace had supported a two- or three-storey building. Unfortunately, the part of the building that once stood on the terrace (as with the stepped-stone structure in the City of David in Jerusalem) is gone forever. However, rooms of the same building complex survive on the plateau to the south, which give a good idea of the date and function of this Cyclopean Terrace complex.

In theory the massive structure could be a Mycenaean temple or fortress, Cosmopoulos admits, but analysis of the finds led him to conclude that it was a powerful palace or administrative center.

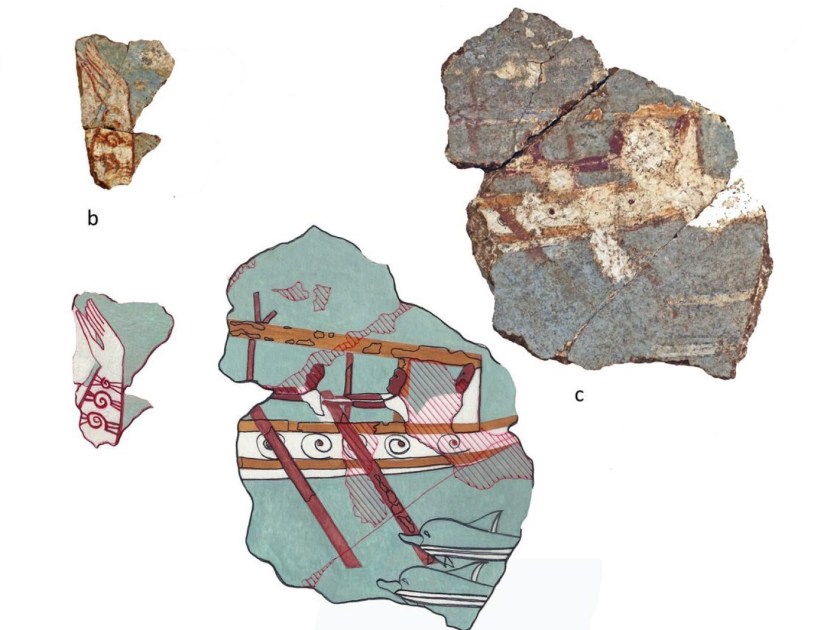

Fragment (right) of an ancient Greek wall painting at a site in Iklaina: The earliest naval representation from the Greek Mainland. Michael Cosmopolous.

“It appears that it was the buildings where the ruler and his family resided, part of the ‘administrative center’ of the site. It was built sometime between 1350 and 1300 B.C.E.,” Cosmopoulos told Haaretz.

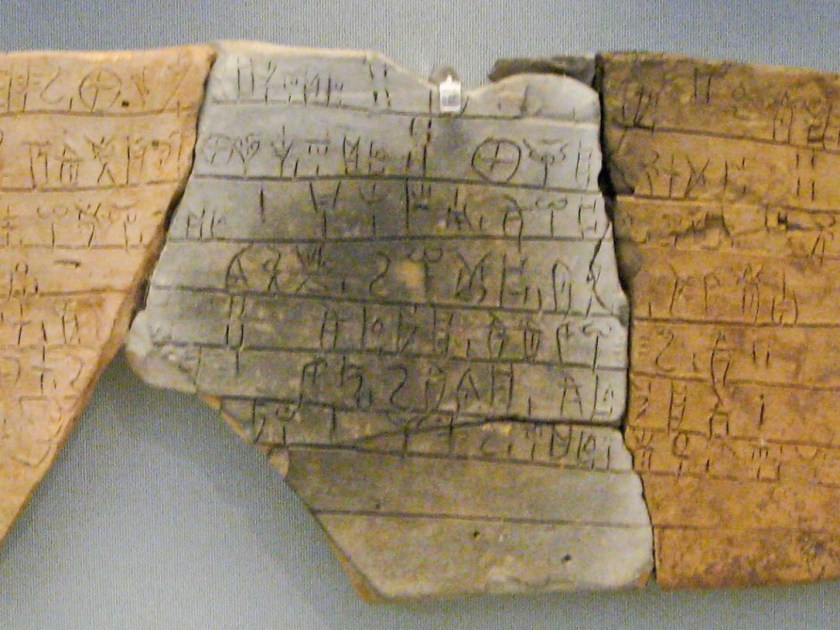

Clay tablet inscribed with Linear B, from the Palace of Nestor in Pylos. It contains information on the distribution of bovine, pig and deer hides to shoe and saddle-makers. Sharon Mollerus, Wikimedia Commons.

No massive structure like this, the construction of which required abundant resources and a great capacity to plan and execute, would have been built in an out-of-the-way and remote settlement. These buildings are monumental and formal, and suggest that Iklaina was the capital of an independent state for a long part of the Mycenaean period – before such states were thought to exist in ancient Greece.

Cosmopoulos’ conclusion is bolstered by the earlier discovery of the tablet containing a bureaucratic record, written in Linear B.

Linear B is a form of writing thought to have descended from an older, still undeciphered writing system known as Linear A, that was used on the island of Crete. Archeologists think Linear A is related to the yet older hieroglyph system used by the ancient Egyptians.

Iklaina tablet, with government record, written in Linear B Michael Cosmopoulous.

Iklaina tablet, with government record, written in Linear B Michael Cosmopoulous.

“The tablet has inscriptions on both sides, on one side a list of male names with numbers (possibly a personnel list), and on the other a list of products – only the heading is preserved, which reads ‘manufactured’ or ‘assembled’. But the tablet is broken and the actual list is missing,” Cosmopoulos said.

The discovery makes it the earliest-known government record in Europe, he says, adding: “But until the final study, we don’t know whether it dates to the period when Iklaina was an independent capital.”

The humiliation of Iklaina

Mainland Greece in the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600-1100 B.C.E.) was divided into independent kingdoms, connected in some kind of loose association, which developed into complex states. All were Mycenaean Greeks and they shared common cultural elements, including architectural types, pottery, religious beliefs, and language, written in Linear B. Iklaina turns out to have been an early example of such a state.

“It appears that the formation of those states was the product of military conflict between powerful rulers. As some rulers became more powerful than others, they started to annex the territories of their neighbors, creating larger and more complex states,” Michael Cosmopoulos told Haaretz.

Aeriel view of Iklaina: This was no backwater but the center of an early complex state. Michael Cosmopoulous.

In any case, after the town’s destruction apparently by the Palace of Nestor, Iklaina was downgraded into an industrial center. Evidence of agricultural produce such as wheat and barley, stock raising of pigs, sheep and goats as well as metallurgy and, possibly, linen production have all been found on site.

Illiterate in Israel?

As for Iklaina’s Linear B tablet, which precedes all others in the region, its discovery has led scholars to revise the assumption that writing was limited to the elite and to the major ruling centers of the time.

Literacy – and mainly, bureaucracy – evidently appeared earlier, and were more widespread across Greece, than had been assumed until now.

It bears mention that other writing systems elsewhere are much older. For example, writings found in China, Mesopotamia, and Egypt are thought to date as far back as 3,000 B.C.E. – over 5,000 years ago. But writing had not been considered widespread in ancient Greece in the 14th century B.C.E. The existence of the tablet, containing government information, not, say, sacred texts legible only to high priests, begs the thought that literacy was not uncommon at the time.

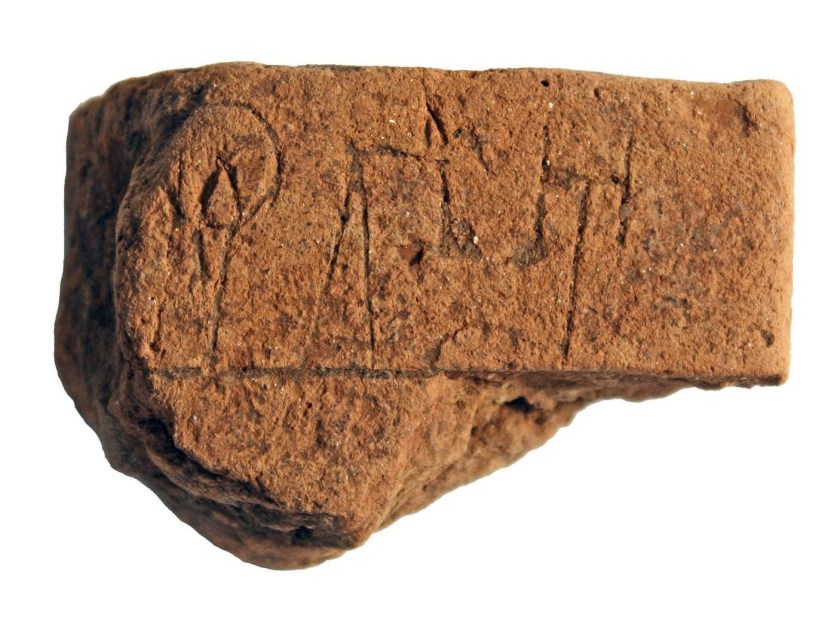

The oldest Hebrew writing found to date, discovered at Khirbet Qeiyafa, the fortress city overlooking a valley where the bible says David slew Goliath. Ronen Zvulun, Reuters.

If literacy was, after all, widespread in Greece in the 14th century B.C.E. and there is evidence of writing from Mesopotamia and Egypt from the 3rd millennium B.C.E, one might ask: Why did Israel and Judah remain illiterate?

One who thinks they didn’t is Allan Millard, professor of Hebrew and ancient Semitic languages at Liverpool University. He even contends that some parts of the Bible could date as far back as the 13th century B.C.E., and that writing was widespread across the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C.E.

“There are scores of brief notes, messages and lists written on potsherds, the ancient scrap paper, from the 8th to early 6th centuries B.C.E. There are a few pieces of writing that may be Hebrew from the 10th and 9th centuries, but the script does not yet have clearly Hebrew features and the texts are too short to be certainly Hebrew. They, along with others, show scribal activity in those centuries,” he told Haaretz.

The sheer number of sites, the quantity of ephemeral texts and the multitude of seals and impressions bearing owners’ names should dispel any notion that writing was rare in early Israel and Judah, Millard argues. And if scribes were employed for legal and administrative duties such as making lists, setting out legal deals and writing letters, it is reasonable to expect some to have spent time writing other texts, as in Mesopotamia and Egypt.