Το Πάσχα ονομάζεται και Λαμπρή η Πασχαλιά, είναι η πιο σημαντική γιορτή του έτους στην Ελλάδα. Το Πάσχα γιορτάζονται τα Πάθη, η Σταύρωση, η Ταφή και τελικά η Ανάσταση του Ιησού Χριστού.

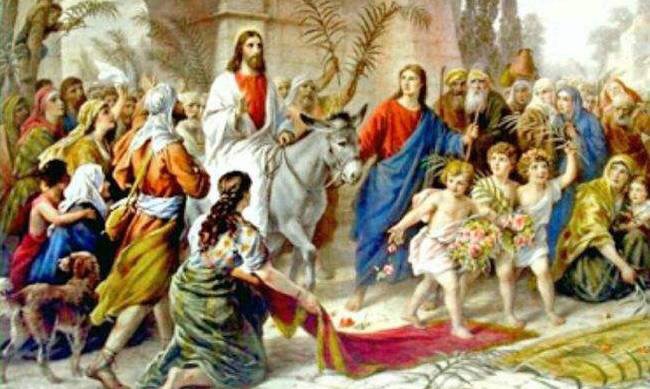

Η κυριότερες ημέρες της Μεγάλης Εβδομάδας αντιπροσωπεύουν και μία απο τις ημέρες που πέρασε ο Ιησούς στην Ιερουσαλήμ απο την ημέρα της εισόδου του στην πόλη των Ιεροσολύμων μέχρι την Ανάσταση του.

Πολλά μέρη στην Ελλάδα γιορτάζουν το Πάσχα με τα δικά τους έθιμα. Μερικά παραδείγματα:

Στην Πάρο τα παιδιά αναπαριστούν τους αποστόλους του Ιησού, τον Μυστικό Δείπνο, την πορεία για τον Γολγοθά και τη Σταύρωση.

Στην Πάτμο δώδεκα μοναχοί αναπαριστούν τους αποστόλους, και ο Ηγούμενος πλένει τα πόδια τους στην πλατεία την Μεγάλη Πέμπτη .

Στην Κρήτη, όπως και σε πολλά σημεία στην Ελλάδα, μια κούκλα κατασκευασμένη από παλιά ρούχα καίγεται συμβολίζοντας το κάψιμο του Ιούδα.

Στην Κέρκυρα ο πολιούχος της πόλης Άγιος Σπυρίδωνας περιφέρεται την Κυριακή των Βαΐων και από το Σάββατο του Πάσχα κεραμικά και κανάτες ρίχνονται στους δρόμους.

Στη Θράκη και τη Μακεδονία νέες γυναίκες φορώντας την παραδοσιακή ενδυμασία που ονομάζεται Λαζαρινή πάνε στα γύρω χωριά τραγουδώντας παραδοσιακά τραγούδια του Πάσχα.

Η Κυριακή των Βαΐων που ειναι και η τελευταία της Σαρακοστής εορτάζει την είσοδο του Χριστού πάνω σε ένα γαϊδουράκι στην Ιερουσαλήμ και την υποδοχή του απο τους κατοίκους της με κλαδιά απο φοινικιές, τα βάγια. Την Κυριακή των Βαΐων μετά την λειτουργία μοιράζονται βάγια και μικροί σταυροί φτιαγμένοι απο φύλλα φοινικιάς.

Η Μεγάλη Δευτέρα ειναι αφιερωμένη στον Ιωσήφ τον πιο αγαπητό υιό του Ιακώβ τον οποίο πούλησαν τα αδέρφια του σε εμπόρους απο την Αίγυπτο. Ο Ιωσήφ εχει μεγάλη σχέση με το Πάσχα γιατί αυτός έφερε τον Λαό του Ισραήλ στην Αίγυπτο οπού και έμειναν αιχμαλωτισμένοι μέχρι την εποχή που ο Μωυσής με την βοήθεια του Θεού τους πήρε απο την Αίγυπτο για να τους φέρει στη Γη Χαναάν.

Το εβραϊκό Πάσχα γιορτάζει το πέρασμα του Αγγέλου που στάλθηκε απο τον Θεό για να θανάτωση όλα τα πρωτότοκα παιδιά των Αιγυπτίων χωρίς να πειράξει τα παιδιά των Ισραηλιτών που είχαν σημαδέψει τις πόρτες των σπιτιών τους με αίμα αρνιού. Την ίδια ημέρα διαβάζεται στην εκκλησία και η παραβολή της καταραμένης συκιάς απο το Ευαγγέλιο του Ματθαίου. Την Μεγάλη Δευτέρα ξεκινούν πολλοί την νηστεία της Μεγάλης Εβδομάδας μέχρι να κοινωνήσουν το Μεγάλο Σάββατο .

Την Μεγάλη Τρίτη διαβάζονται η παραβολή των δέκα Παρθένων πού όταν άκουσαν το ιδού ο Νυμφίος έρχεται έτρεξαν να συναντήσουν τον Νυμφίο, όμως οι πέντε απο αυτές, οι Μωρές, είχαν αποκοιμηθεί και αργοπόρησαν να βάλουν λάδι στα φανάρια τους, έτσι τελικά δεν μπόρεσαν να πάνε στο Γάμο, το δίδαγμα αυτής της παραβολής ειναι ότι οι άνθρωποι πρέπει να ειναι πάντα έτοιμοι για την βασιλεία των ουρανών. Η παραβολή του πλούσιου άρχοντα και των τριών υπηρετών του και ο τρόπος που διαχειρίστηκαν τα χρήματα που τους άφησε διδάσκουν την αγαθοεργία που πρέπει να έχουν οι άνθρωποι. Το βράδυ ψάλετε το τροπάριο της Κασσιανής.

Την Μεγάλη Τετάρτη διαβάζεται το Μύρωμα του Ιησού απο την αμαρτωλή, Ο Χριστός μιλάει ήδη για τον επερχόμενο θάνατο του λέγοντας στους μαθητές του ότι η γυναίκα τον μύρωσε για να τον προετοιμάσει για την ταφή του. Στη λειτουργία ψάλετε ο Ευχέλαιος.

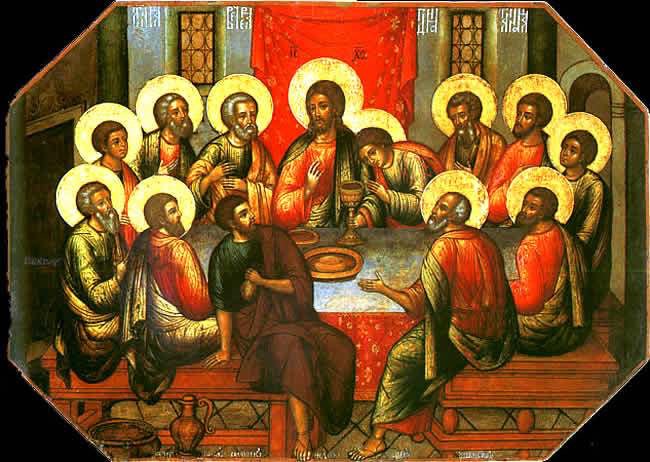

Την Μεγάλη Πέμπτη το Θειο Δράμα προχωρεί προς την αποκορύφωση του, την ημέρα αυτή γίνεται ο Μυστικός Δείπνος όπου ο Ιησούς κοινωνεί τους μαθητές του δίνοντας τους απο ενα κομμάτι ψωμί που συμβολίζει το σώμα του και κρασί που συμβολίζει το αίμα του. Απο αυτήν την πρώτη κοινωνία των μαθητών ξεκινά το μυστήριο της Θείας κοινωνίας.

Το ίδιο βράδυ ο Ιησούς γυρνώντας στους μαθητές τους λέει ότι κάποιος απο αυτούς θα τον προδώσει, ο Ιούδας φεύγει για να ετοιμάσει την προδοσία του κι ο Ιησούς συλλαμβάνεται στον κήπο της Γεσθημανής όπου εχει πάει για να προσευχηθεί με τους μαθητές του. Το βράδυ ψέλνονται τα Δώδεκα Ευαγγέλια και στην εκκλησία περιφέρεται ο Σταυρός με τον Ιησού.

Σημείωση: Η αναζήτηση του Αγίου Δισκοπότηρου με το οποίο ο Ιησούς ευλόγησε και έδωσε να πιουν κρασί οι μαθητές του, έγινε για τους δυτικούς και ειδικά για τους σταυροφόρους ένας θρύλος και μια απο τις δικαιολογίες τους για τις εκστρατείες τους για την απελευθέρωση των Αγίων τόπων απο τους Άραβες.

Η μεγάλη γιορτή του Πάσχα ξεκινά τη Μεγάλη Παρασκευή που συμβολίζει τα συμβάντα της δίκης του Ιησού απο τον Πόντιο Πιλάτο , την μαρτυρική πορεία Του προς τον Γολγοθά, την Σταύρωση του και τελικά την Ταφή του. Ο Επιτάφιος βρίσκεται στην εκκλησία στολισμένος με ανοιξιάτικα λουλούδια. Μετά το τέλος της Λειτουργίας κάθε ενορία γυρνά τον επιτάφιο στην περιφέρεια της, σε μερικές εκκλησίες απλώς περιφέρεται γύρω απο την εκκλησία. Ήδη σε πολλές περιοχές της Ελλάδας τα πρώτα πυροτεχνήματα εμφανίζονται την βραδιά του επιτάφιου.

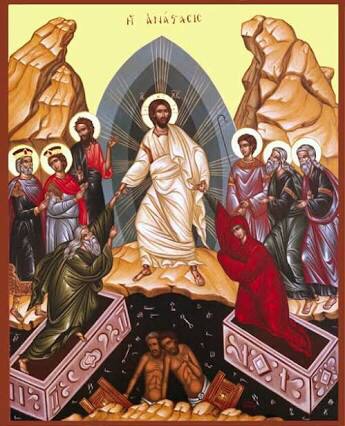

Το Μεγάλο Σάββατο ειναι η γιορτή της Ανάστασης, σε πολλές εκκλησίες με την πρωινή λειτουργία της πρώτης Ανάστασης πέφτουν και πολλά πυροτεχνήματα, η μεγάλη λειτουργία της Ανάστασης και το αποκορύφωμα γίνεται τα μεσάνυχτα, ο κόσμος πηγαίνει στην εκκλησία αργά το βράδυ μεταφέροντας μαζί λαμπάδες και κεριά.

Τα μεσάνυχτα τα φώτα της εκκλησίας σβήνουν και ο ιερέας ψάλει το Δεύτε Λάβετε Φώς (Το Άγιο Φώς κάθε χρόνο φτάνει με ειδική πτήση της Ολυμπιακής απο τα Ιεροσόλυμα και μοιράζεται σε όλες τις εκκλησίες της Ελλάδας) . Μετά ακολουθεί το Αναστάσιμο Ευαγγέλιο, συνήθως στο προαύλιο της εκκλησίας, ο Ιερέας σηματοδοτεί την Ανάσταση του Χριστού ψάλλοντας το Χριστός Ανέστη.

Ο κόσμος σπάει κόκκινα αυγά και εύχεται Χριστός Ανέστη, φωτοβολίδες και πυροτεχνήματα φωτίζουν τον ουρανό. Κατα την επιστροφή στο σπίτι πολλοί φτιάχνουν ένα σταυρό πάνω απο την πόρτα με την αιθάλη του κεριού. Το τραπέζι ειναι στρωμένο με την παραδοσιακή μαγειρίτσα, κόκκινα αυγά και πασχαλιάτικες λιχουδιές.

Η Κυριακή του Πάσχα ειναι η μεγάλη γιορτή της Λαμπρής, απο νωρίς το πρωί ο παραδοσιακός οβελίας ψήνεται στη σούβλα ενώ γύρω απο το εορταστικό τραπέζι γλεντούν οικογένειά και φίλοι με τραγούδια και χορό.

Το Πασχαλινό Τραπέζι και ‘Aλλα Έθιμα

Τα Πασχαλινά φαγητά στην κεντρική και ανατολική Ευρώπη προετοιμάζονται εκ των προτέρων, και ευλογούνται από τον παπά προτού τα δοκιμάσει κανείς. Η παράδοση του Πασχαλινού Αμνού εξασφαλίζει αξιοζήλευτη θέση στο Πασχαλινό τραπέζι, αν και σε μερικές χώρες ένα γλύκισμα μπορεί να γίνει το υποκατάστατό του.

Στην Πολωνία το αρνί φτιάχνεται από βούτυρο και περιστοιχίζεται από πολυάριθμα πιάτα που περιέχουν ζαμπόν, ψητό μοσχάρι, λουκάνικο και άλλες λιχουδιές. Σαν γενικός κανόνας το τραπέζι διακοσμείται όμορφα με λινό τραπεζομάντιλο, λουλούδια και γιρλάντες.

Εθιμοτυπικά χρησιμοποιείτο μια εποχή το ξινό βότανο για να δώσει άρωμα στα Πασχαλινά κέικ και τις πουτίγκες.

Σπάνια χρησιμοποιείται στις μέρες μας, εξαιτίας της πικρής του γεύσης που αρχικά συμβόλιζε τα πικρά βότανα του Εβραϊκού Πασχαλινό γεύματος.

Στην Αγγλία μια κόκκινη ρέγγα, που μοιάζει σαν έναν άνθρωπο πάνω στη ράχη αλόγου, στη βάση ενός καλαμποκιού, τρώγεται την Ημέρα του Πάσχα, ενώ τα ραπανάκια ήταν η σπεσιαλιτέ της εποχής.

Στην Πολωνία τα αγόρια της επαρχίας παίρνουν ένα δοχείο χυλού –φτιαγμένο από νερό αναμιγμένο με σίκαλη και μαγιά- και μια ρέγγα, και το κάνουν ταμπούρλο έξω από το χωριό πριν το θάψουν. Επειδή οι πιστοί ζούσαν με ελάχιστα την περίοδο της νηστείας, τα αγόρια διασκέδαζαν κάνοντας την κηδεία της τροφής.

Οι Ρώσοι ετοιμάζουν το πάσκα, ένα ψηλό, άκαμπτο ψωμί, φτιαγμένο με σπιτικό τυρί και ξερές σταφίδες γλασαρισμένο στη κορφή. Οι Ιταλίδες μητέρες δίνουν στα παιδιά τους τη τσιαμπέλα, ένα κέικ φτιαγμένο με ελαιόλαδο όπου: στα αγόρια δίνεται στο σχήμα ενός αλόγου, ενώ στα κορίτσια στο σχήμα ενός περιστεριού στολισμένο με πραγματικά φτερά. Τα παιδιά της Αυστραλίας παίρνουν ένα κέικ σε σχήμα φωλιάς γεμισμένο με αυγά. Μερικοί λόγιοι βλέπουν σε τέτοια εθιμοτυπικά γλυκίσματα τα υπολείμματα ενός παλαιού μαγικού τυπικού, όπου τελετουργικές προσφορές ψωμιού εξασφάλιζαν ευημερία στην κοινότητα και στη φυλή.

Μερικές φορές τα γλυκίσματα ήταν τμήμα μιας ελεημοσύνης ή φιλανθρωπικής διανομής, όπου εκπλήρωναν μια πραγματική ανάγκη σε καιρούς όπου η φτώχεια σήμαινε λιμοκτονία. Ελαφρώς διαφορετικές ήταν και οι Εκκλησιαστικές Μπύρες, που δίνονταν σε μερικά μέρη της Βρετανίας την ίδια εποχή. Στην Εβραϊκή γιορτή θυσιάζονταν αρνιά για να εορταστεί η απελευθέρωση του Ισραήλ από τη δουλεία στην Αίγυπτο, ενώ στη Χριστιανική παράδοση αντιπροσωπεύει ο πασχαλινός αμνός τον Χριστό. Μια άλλη άποψη τοποθετεί τον αμνό σε μια ποιμενική γιορτή, επρόκειτο για τη θυσία ενός αρνιού έτσι ώστε ο θεός των ποιμνίων-της γονιμότητας, να πάρει το μερίδιό του για να εξασφαλίσει τη γονιμότητα του ποιμνίου. Το αρνί τρωγόταν σε ένδειξη κοινωνίας με το θεό προστάτη.

Οι προετοιμασίες για το ορθόδοξο δείπνο της Ανάστασης ξεκινούν από το Μεγάλο Σάββατο το πρωί δίνοντας τέλος στη νηστεία της Μεγάλης Εβδομάδας. Αν και αρκετοί ήταν αυτοί που κάθονταν στην αναστάσιμη λειτουργία το βράδυ του Σαββάτου υπήρχαν πολλοί που κατέληγαν στο τραπέζι της αγάπης για την ελαφριά σούπα από κοτόπουλο, η οποία αντικαταστάθηκε σε πολλούς τόπους από την παραδοσιακή μας μαγειρίτσα, μια σούπα φτιαγμένη από τα σπλάχνα του αρνιού, ρύζι και αρωματικά βότανα αλλά και τα σκαλτσούνια ή μελιτίνια, τα συνοδευτικά γαρδουμπάκια, συκωταριά, ψητό κρέας, κόκκινα αυγά καθώς και πολλών άλλων φαγητών με τοπικό χαρακτήρα.

Το τραπέζι της Κυριακής του Πάσχα είναι από τα πλουσιότερα. Με αγάπη το γεμίζουν από όλα τα καλά, με λαμπροκουλούρες, καλτσούνια, λαζαράκια, τσουρέκια, αυγά κ.α. Όλοι μαζί, φίλοι και συγγενείς, ψήνοντας το αρνί ή το κατσίκι και το κοκορέτσι πίνουν και γλεντούν γιορτάζοντας την ανάσταση. Το αρνί αποτελεί ένα κατεξοχήν μυθικό σύμβολο, με την έννοια της αθωότητας και της αγνότητας κυρίως σε πνευματικό επίπεδο, έτσι με τον διαμελισμό του επιτρέπει στους ανθρώπους την επικοινωνία με αυτή την αγνότητα. Το «παραδοσιακό» Πασχαλινό τραπέζι διαφέρει από περιοχή σε περιοχή, αν και σε όλη τη χώρα αντικατοπτρίζει την ίδια αρχαία σοφία: «τίποτα δεν πάει χαμένο». Αν κάποιος έχει νηστέψει για 40 ολόκληρες ημέρες, απέχοντας από κρέας και γαλακτοκομικά, τότε η ιδέα να γευτεί και την τελευταία μπουκιά είναι ακόμη πιο σημαντική. Τέλος ένα έθιμο του Πάσχα που έρχεται από τα αρχαία χρόνια, πριν την γέννηση του Χριστού, είναι το διάβασμα της «κουτάλας» του αρνιού δηλ. της ωμοπλάτης του ζώου, που λεγόταν ότι με αυτό μπορούσε ο νοικοκύρης του σπιτιού να προβλέψει το μέλλον.

Το απόγευμα της ίδιας ημέρας διαβάζεται το Ευαγγέλιο της Ανάστασης σε εφτά γλώσσες. Αποτελεί τη «Λειτουργία της Αγάπης» και εκφράζει το ύψιστο μήνυμα της Ανάστασης του Χριστού. Σε πολλές περιοχές βραδιάζοντας καίνε ένα ομοίωμα του Ιούδα. Οι νέοι φτιάχνουν το ομοίωμα από παλιά χαλιά, βάζουν στα χέρια του τα τιμαλφή της προδοσίας, μια σακούλα με 30 νομίσματα, και το κρεμούν στην αυλή μέχρι να καεί.

Η ανανέωση και το ξανάνιωμα, που είναι στενά συνδεδεμένα με το κεντρικό νόημα του Πάσχα, συμβολίζονται με πολλούς τρόπους. Σύμφωνα με μια κοινή και ευρέως διαδεδομένη πίστη, το τρεχούμενο νερό γίνεται ευλογημένο την Ημέρα του Πάσχα επειδή ο Χριστός το καθαγίασε. Στη Γαλλία οι γυναίκες πλένουν το πρόσωπό τους στα ρυάκια ενώ σε άλλες χώρες οι αγρότες ραντίζουν τα ζώα τους. Μπουκάλια πασχαλινού νερού συχνά διατηρούνται προσεκτικά ως μια πηγή θεραπείας, ενώ στην Ιρλανδία λέγετε πως το συγκεκριμένο νερό τους παρείχε προστασία από τα κακά πνεύματα.

Το νερό είναι σημαντικό στο να βοηθήσει τις σοδειές να αναπτυχθούν, και οι πρωτόγονοι λαοί θεωρούσαν ότι αυτό κατείχε για γενικότερη γονιμοποιό επίδραση. Σε κάποιες Ευρωπαϊκές χώρες είναι σύνηθες να ραντίζουν κορίτσια και αγόρια. Στην Ουγγαρία αυτό λαμβάνει χώρα τη Δευτέρα του Πάσχα. Το ίδιο έθιμο υπήρχε στην Πολωνία, σήμερα μερικές σταγόνες κολόνιας ή ροδόνερου αντικαθιστούν το παλαιομοδίτικο κατάβρεγμα. Στο Μεσαίωνα πραγματοποιείτο μία διήμερη εορτή, όπου αφού πετούσαν νερό κορίτσια και αγόρια έριχναν ο ένας στον άλλο αυγά.

Μερικά Πασχαλινά έθιμα έχουν άμεσους δεσμούς με τυπικά ανάπτυξης της σοδειάς. Μία δημοφιλής ιεροτελεστία αποτελείται από το άγγιγμα ενός νεαρού ή νεαρής με το κλαδί ενός δέντρου. Αυτό έδινε υγεία και γονιμότητα. Στην Τσεχοσλοβακία η Πασχαλινή Βέργα πλέκεται με κλαδιά ιτιάς και διακοσμείται με κορδέλες. Ένα αγόρι θα χτυπούσε ένα κορίτσι στα πόδια με αυτή μέχρι να του δώσει πρόστιμο Πασχαλινά αυγά. Στην ανατολική Πομερανία της Γερμανίας, προς μεγάλη μας έκπληξη, τα παιδιά κυνηγούσαν τους γονείς να σηκωθούν από το κρεβάτι, χρησιμοποιώντας ένα κλαδί σημύδας. Στη Μακεδονία, τα κορίτσια ξυπνούν νωρίς το πρωί του Πάσχα, βρίσκουν μια κερασιά και φτιάχνουν μια κούνια. Αργότερα, και άλλες κούνιες ορθώνονται στο πράσινο του χωριού και η χόρα, ένας αρχαίος κυκλικός χορός, εκτελείται ενώ γίνεται η αιώρηση. Παρατηρείται κάτι αντίστοιχο και σε άλλες περιοχές όπως το Πήλιο, τη Μυτιλήνη και τη Σάμο. Οι κούνιες αποτελούν αρχαίο έθιμο και θυμίζουν την «αιώρα» των Αθηναίων παρθένων στα Ανθεστήρια, μια από τις λαϊκότερες γιορτές στις αρχές της ‘Aνοιξης. Ένα παρόμοιο παιχνίδι ήταν δημοφιλές στη Λετονία, η αρχική πρόθεση πιθανώς ήταν να ενθαρρύνει τις σοδειές να αναπτυχθούν τόσο ψηλά όσο αιωρούνταν τα κορίτσια.

Παραδοσιακά η εργασία απαγορευόταν στην Πολωνία κατά τη διάρκεια της Μεγάλης Εβδομάδος, ιδιαίτερα την Πέμπτη, η οποία είναι αφιερωμένη στη μνήμη των νεκρών. Λένε ότι ένας αγρότης που επέμενε να οργώνει τα χωράφια του τον κατάπιε η γη μαζί με τα βόδια του. Οποιοσδήποτε βάλει το αυτί του στο έδαφος θα τον ακούσει να καλεί σε βοήθεια. Μερικοί άνθρωποι απέφευγαν τη δουλειά με το λινό ή τα νήματα, όντας η παράδοση ότι, η σκόνη από αυτά τα υλικά θα έμπαινε στα μάτια των νεκρών. Προφανώς υπάρχει κάποια σύνδεση με τα σάβανα της κηδείας.

Η επίδραση όμως των τελετουργιών της αρχαίας Ελλάδος στο χριστιανισμό φαίνεται ότι είναι μεγαλύτερη από όσο οι περισσότεροι γνωρίζουμε. Για παράδειγμα το Πάσχα στην Αρχαία Ελλάδα γιόρταζαν τα «Αδώνια», κατά τα οποία γινόταν αναπαράσταση του θανάτου του ‘Aδωνι. Οι γυναίκες στόλιζαν το νεκρικό κρεβάτι με λουλούδια και καρπούς ενώ τραγουδούσαν μοιρολόγια. Ακολουθούσε επιτάφιος πομπή, ενώ την επομένη ημέρα γινόταν η ανάσταση του ‘Aδωνι, που συμβόλιζε την καρποφορία της φύσης.

Αλλά και η μετάληψη με το «θείο» σώμα και αίμα ήταν μέρος των τελετουργιών, τόσο των Κορυβαντικών όσο και των Ορφικών μυστηρίων. Στη μετάληψη των Ορφικών οι πιστοί, επιδίδονταν σε ωμοφαγία ταύρου και οινοποσία, που συμβόλιζε το σώμα και το αίμα του Διόνυσου Ζαγρέα. Πίστευαν ότι με αυτόν τον τρόπο κατέρχονταν σε αυτούς η θεότητα και γέμιζε τις ψυχές τους. Στα Κρητικά μυστήρια, η προσφορά του Διόνυσου Ζαγρέα και η θυσία του Μινώταυρου, ήταν η θεία Δωρεά, η κάθοδος της πνευματικής δύναμης, του συμβολικού ταυρείου αίματος. Αυτό το έθιμο αφού πέρασε από διάφορα στάδια στα ελληνικά Μυστήρια των ιστορικών χρόνων αλλά και στα Μιθραϊκά των Περσών πέρασε και στα Χριστιανικά στους μετέπειτα αιώνες.

Ένα άλλο έθιμο των ημερών είναι τα πασχαλινά κόκκινα αυγά, τα οποία συμβολίζουν το αίμα του Ιησού Χριστού, όταν οι στρατιώτες Τον λόγχιζαν επάνω στο σταυρό. Σύμφωνα όμως με τον Κοραή τα κόκκινα αυγά, συμβολίζουν το αίμα των προβάτων με το οποίο οι Ιουδαίοι έβαψαν τις οικείες τους, για να αποφύγουν την «υπό εξολοθρευτικού Αγγέλου φθοράν». Οι αρχαίοι Αιγύπτιοι και οι Γαλάτες πρόσφεραν βαμμένα αβγά για να γιορτάσουν την άνοιξη. Όπως αναφέρει ο Γ. Α. Μέγας, χρωματιστά κυρίως κόκκινα αυγά, μνημονεύονται ήδη από τον 5ο αι. στην Κίνα για γιορταστικούς σκοπούς και στην Αίγυπτο από τον 10ο αι. Ενώ τον 17ο αι. τα βρίσκουμε στους Χριστιανούς και τους Μωαμεθανούς, όπως στη Μεσοποταμία και τη Συρία, έπειτα στην Περσία και τη Χερσόνησο του Αίμου. Μερικοί υποθέτουν ότι τα κόκκινα αυγά του Πάσχα διαδόθηκαν, σε όλη την Ευρώπη και την Ασία και συνδέθηκαν με τα τοπικά έθιμα των λαών.

Το τσούγκρισμα των πασχαλινών αυγών, συμβολίζει την Ανάσταση του Χριστού, καθώς το αυγό συμβολίζει τη ζωή και τη δημιουργία που κλείνει μέσα του ζωή. Όταν το κέλυφος του αυγού σπάσει με το τσούγκρισμα, γεννιέται μια ζωή, έτσι παρομοιάζει το σπάσιμο του τάφου του Χριστού και την Ανάστασή Του.

Το αυγό βέβαια σε όλες σχεδόν τις αρχαίες κοσμογονίες σήμαινε την γέννηση του σύμπαντος και της ζωής. Χαρακτηριστικό παράδειγμα το σύμβολο των ορφικών Μυστηρίων που ήταν ένα φίδι τυλιγμένο γύρω από ένα αυγό, που συμβόλιζε τον κόσμο που περιβάλλεται από το Δημιουργικό πνεύμα. Στο επίπεδο της μύησης και της φιλοσοφίας, αντιπροσώπευε τον νεόφυτο που την στιγμή της μύησής του έσπαγε το κέλυφος του αβγού και ένας καινούργιος πνευματικός άνθρωπος γεννιόταν.

Το τσουρέκι, η γνωστή μας λαμπροκουλούρα ζυμώνεται για το καλό. Οι αγρότες παραχώνουν κομμάτια τσουρεκιού και τσόφλια αυγών στα χωράφια τους για να ευλογηθεί η σοδειά τους. Οι νοικοκυρές στη Σίφνο ετοιμάζουν τα παραδοσιακά «πουλιά» και πασχαλινές κουλούρες σε διάφορα σχήματα ζώων και πουλιών, στολισμένα με κόκκινα αβγά.

Τα πιο γνωστά είναι φυσικά η πλεξούδα, με ή χωρίς κόκκινο αβγό. Οι πλεξούδες και οι κόμποι προέρχονται από τους ειδωλολατρικούς χρόνους ως σύμβολα για την απομάκρυνση των κακών πνευμάτων. Ζύμωναν με μυρωδικά τις κουλούρες της Λαμπρής και τις στόλιζαν με λουρίδες από ζυμάρι και ξηρούς καρπούς. Παρόμοιες κουλούρες έφτιαχναν και στα βυζαντινά χρόνια, τις «κολλυρίδες», που ήταν ειδικά ψωμιά για το Πάσχα σε διάφορα σχήματα με ένα κόκκινο αυγό στο κέντρο τους.

Τα σοκολατένια πασχαλινά κουνελάκια, αποτελούν ίσως τη μεγαλύτερη χαρά των παιδιών, στην εορτή του Πάσχα. Αρχικά, το πασχαλινό κουνελάκι ήταν λαγός. Για τους Σάξονες ο λαγός ήταν το έμβλημα της θεάς Eastre, την οποία τιμούσαν την άνοιξη. Από αυτήν άλλωστε προέρχεται η λέξη Easter, που σημαίνει Πάσχα στα αγγλικά. Για τους Κέλτες και τους Σκανδιναβούς ο λαγός αποτελούσε επίσης το σύμβολο της θεάς της μητρότητας και της ανοιξιάτικης γονιμότητας. Το παραδοσιακό κουνελάκι που φέρνει αβγά στα παιδιά είναι γερμανικής προελεύσεως.

Μια σειρά από ιστορικά γεγονότα, πνευματικές εμπειρίες, έθιμα και κυρίως το «πάντρεμα» διαφορετικών πολιτισμών, αναβιώνουν και κυριαρχούν τις άγιες αυτές ημέρες. Ο συμβολισμός τους έχει ως σκοπό, την απόδοση του θείου δράματος, αλλά και τη λυτρωτική κατάληξη με την Ανάσταση του Θεανθρώπου.

Η Σταύρωση και η Ανάσταση του Χριστού αποτελεί τη μετάβαση του ανθρώπου από το Θάνατο στη Ζωή. Ο Χριστός «ανέστη εκ νεκρών» και καταπάτησε τον Θάνατο. Με την Ανάστασή Του θα αναστήσει όλο το γένος από κάθε είδους μορφής σκλαβιάς καθοδηγώντας το σε Αναγέννηση. Θα φέρει τέτοια πνευματική διέγερση με τα πάθη του, που θα οδηγήσει την ανθρωπότητα σε μια νέα συνειδησιακή διεύρυνση.

Αντιλαμβανόμαστε το λόγο της ύπαρξής μας και τις δικές μας ευθύνες προς τη Ζωή, ως σύνολο. Η αναγκαιότητα της δικής μας ανάστασης ωθεί σε μια διεύρυνση της συνείδησης, διεύρυνση και επίγνωση της ευθύνης που έχουμε για την πνευματική ανάσταση της ανθρωπότητας και του πλανήτη.